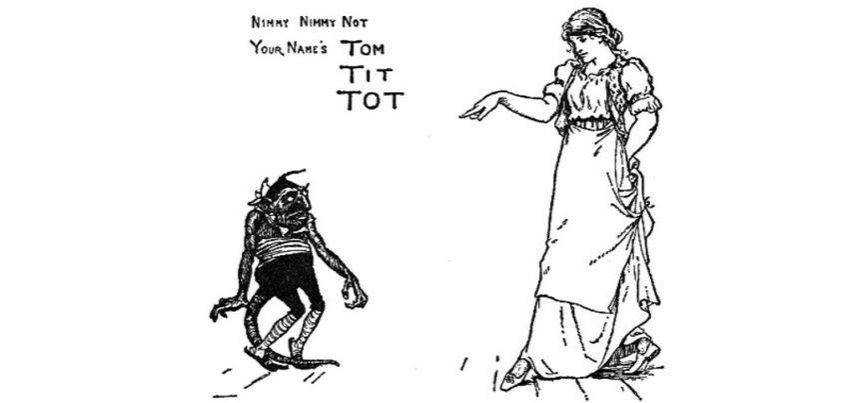

The protagonist in Tom Tit Tot is a lazy girl who doesn’t appear to be good at anything except eating. Her mother lies to the king by saying she is a whiz with the spinning wheel. For some reason this is just the kind of girl the king is looking to marry. The poor girl can’t even spin a top, so in order to avoid losing her head she accepts an offer of help from a small magical creature. As the creature helps the girl, she must try to guess its name. If she can’t, she shall become “its”.

The protagonist in Tom Tit Tot is a lazy girl who doesn’t appear to be good at anything except eating. Her mother lies to the king by saying she is a whiz with the spinning wheel. For some reason this is just the kind of girl the king is looking to marry. The poor girl can’t even spin a top, so in order to avoid losing her head she accepts an offer of help from a small magical creature. As the creature helps the girl, she must try to guess its name. If she can’t, she shall become “its”.

Our source for the story was a children’s book called English Fairy Tales by folktale collector Joseph Jacobs, first published in 1890. In the book, Jacobs wrote: “The story of Tom Tit Tot …is one of the best folktales that have ever been collected, far superior to any of the continental variants of this tale with which I am acquainted.” The folktale may have other merits. However, if Jacobs was talking about its storyline, the European versions (the best known being the Grimm Brothers’ Rumpelstiltskin) win hands down.

Tom Tit Tot Full Text / PDF / Audio (1,700 words)

Rumpelstiltskin Full Text / PDF / Audio (1,100 words)

Jacobs’ source was a folktale of the same name which appeared in the ‘Suffolk Notes and Queries’ section of the Ipswich Journal in 1877. This and another story featured on our website, Cap O Rushes, were contributed by Victorian poet Anna Walter-Thomas (née Fison), who wrote that she heard them from her nurse as a child.

After Tom Tit Tot was published, British folktale enthusiast Edward Clodd became so excited about it that he wrote a book (Tom Tit Tot: An Essay on Savage Philosophy in Folk-tale) exploring how parts of the story may reflect various ancient beliefs and customs. In referring to the two Walter-Thomas stories, Clodd commented in a rather condescending tone that: Much of their value lies in their being almost certainly derived from oral transmission through uncultured peasants.

Herein lies the root of Tom Tit Tot‘s differences with the so-called ‘continental variants’.

The Grimm Brothers researched multiple sources and often combined similar stories into a single, easy to read whole. Rumpelstiltskin flows logically and the premise (a greedy king wanting a girl who can spin straw into gold) is easy to believe. Tom Tit Tot comes from a single source, and leaves a number of unanswered questions which greatly reduce its dramatic effect. For example: Why does the king want a wife who can spin five skeins of flax every day? Why not put her to the test first rather than waiting until they have been married for eleven months and then (especially if there was a child on the way) potentially having to kill her? And what exactly did the little creature mean when he told the girl that if she can’t guess his name you shall be mine?

It is likely that there was more to the Tom Tit Tot story than the version reported in the Ipswich Journal. As we have pointed out before, stories handed down by oral transmission are like the children’s game ‘Chinese Whispers’; they change slightly with each re-telling.